Manual reproduction of data over time has created a wealth of misinformation…perhaps.

One of my least favorite tasks involves copying the technical information of a new acquisition into a database. It is tedious, uninspiring, and a burden on my macro-thinking tendencies. Additionally, it foments human error. In the 21st Century, should we be copying artist biographical data into a database?

If you are lucky enough, you have the documents digitally, and can mostly copy and paste, but every database differs in how they treat the information. Once you pass the basic tombstone information, you arrive at more detailed categories such as exhibition history or bibliography which rarely present themselves uniformly or enter into a database in a consistent manner. As a result, one must meticulously oversee the details of each entry. Further, a small typo renders a search unresponsive. For example, if I enter in a Picasso exhibition like “Picaso: Blue Period” and forget the second ‘s’, then I undermine the point of the entry as it fails to appear when I search “Picasso”.

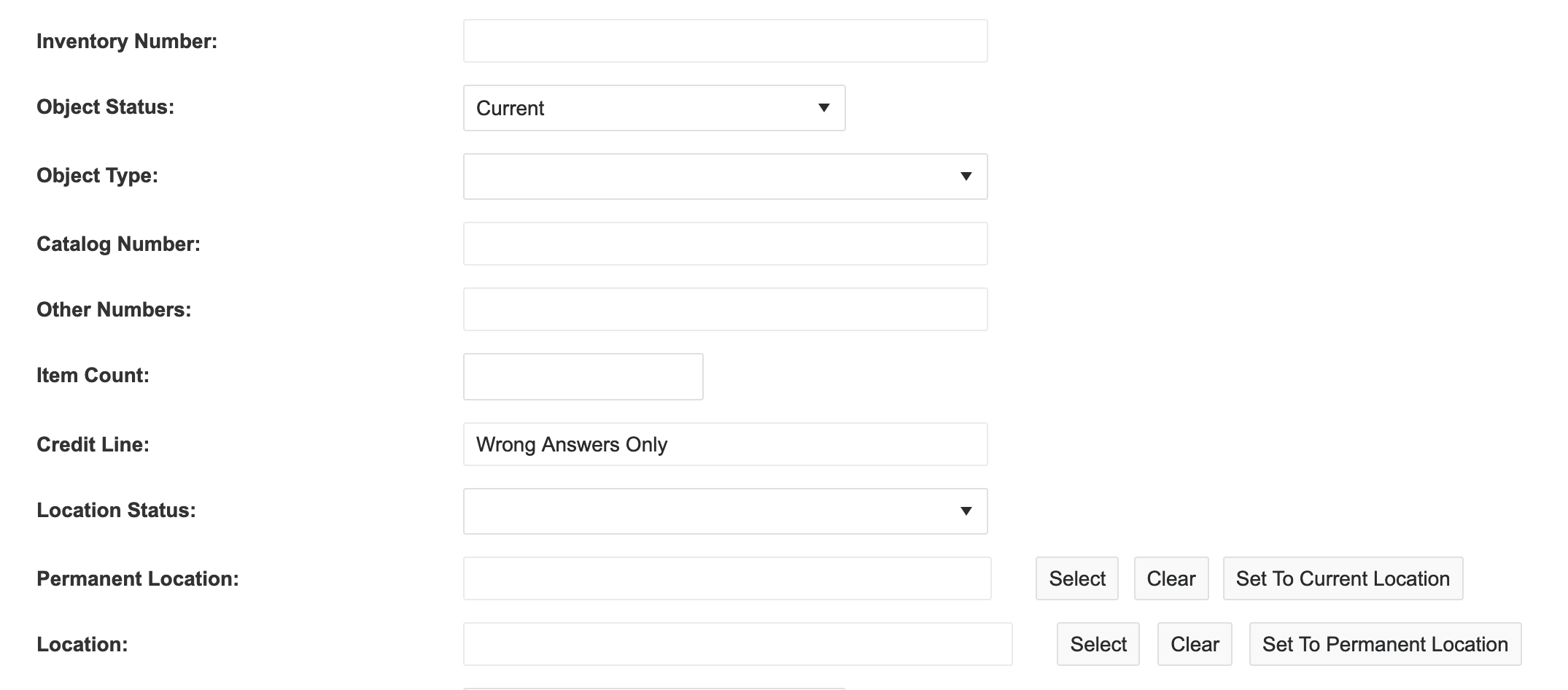

Some databases combat such instances with drop-down menus for common entries like “Oil on canvas”, an artist’s name, or if luck prevails, an auto-fill function not unlike in Excel.

Anyone working with databases and in registration for a while already understands this issue, but have we considered a solution? How much of our data has metastasized from mostly accurate to questionable? A digital game of telephone.

Actually, if we regularly access the data, we probably regularly update and correct it. Thus, I imagine that for institutions managing lots of data with dedicated professionals working on their most known objects, perhaps the majority of the data represents the best possible version of itself. We never really know, however.

Behind this questioning, though, lies the implications of how we use the data. Registrars are a half-step away from evolving into data scientists. While we input and manage the data, we do not yet aggressively use it to make decisions (correct me if I have this wrong). Microsoft offers this definition of a data scientist:

A data scientist leads research projects to extract valuable information from big data and is skilled in technology, mathematics, business, and communications. Organizations use this information to make better decisions, solve complex problems, and improve their operations. By revealing actionable insights hidden in large datasets, a data scientist can significantly improve his or her company’s ability to achieve its goals. That's why data scientists are in high demand and even considered "rock stars" in the business world.

What “actionable insights” could your database reveal?

IBM more elaborately explains data science in this way.

This road paved with ones and zeros leads us to next level actions. Once you start using data science to reveal trends within you collections’ management, one might tend to just aggregate more and more data to the dataset. In other words, now we aggregate data from our database but also our digitized files and, indeed, all data to which we have access. It, thus, influences our data collection habits and practices.

Last week, I used ChatGPT to most likely inaccurately predict what will happen in the world of art and artifact collections in 2023. The power of ChatGPT implicates a future where our databases safely use the already existing data to fill in much of the basic information about an object. Personally, when cataloging works, I already have to search online for information about, say, an exhibition to get the exact dates or find other random bits of information to fill out a record. Artificial intelligence already has the capacity to find this for you and machine learning will make it increasingly more accurate like adding more numbers to the end of pi. It just depends on the level of access to the available data.

Returning to my previous example, if our institution acquires a work by Picasso and we begin filling in the title, with the available information it can theoretically enter in everything that it can already access online or that it was fed. Even for data contained in physical records, like a catalogue raisonné, Google continues to digitize physical print books. This all assumes we can safely connect our databases to the internet and that we can still protect and control our data.

I see data entry as a baby step. The real changes comes when we interpret and react to the data. Most major business already use artificial intelligence and machine learning to make decisions to create better efficiencies and improve performance in order to maximize profits and provide a better user experience. Museums and other cultural institutions will follow. If music and video streaming services, for example, can instantly generate a playlist or recommendation based on your respective listening and viewing history, why not reduce the need for expensive curators and let the AI curate shows? It sounds harsh, but optics may be the primary barrier to it. Nevermind, this has already started; some call it Instagram.

I will also add that others have come to this conclusion independently. See this case study on which Artnews meditated.

The rise of robotics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning could have devastating consequences even for professionals as humanistic as museum curators. As art institutions continue to raise ticket prices and roll out blockbusters, we may come to see shows that will be curated entirely by optimized algorithms.

From a purely collections management point of view, imagine all the shipping data, exhibition data, tracker data, and the datalogger data you accumulate, and consider how you can use it to make decisions about the health of an object, the use of the collection, the mitigation of risk, the efficiency of storage, the monetary value of the objects, or the scope of the collection.

And, breaking the sound barrier, imagine what a goliath database company, a prominent shipping company, or a multi-billion-dollar auction house, who can access ALL of the data from some of the biggest institutions in the world (its clients), could do with that amount and depth of information. AI could draw significant conclusions from analyzing it, and those conclusions could radically affect our job descriptions and the management of our collections. Of course, those conclusions depend on the accuracy of the data we have already released from captivity and mined by our algorithms.