A constellation of recent discussions relating to art and artifact collections management.

May screened some big episodes this month in the ongoing drama that composes the management of cultural patrimony. The story of the Met’s mummy repatriation, Warhol and Prince “collaboration”, and an art fraud Ponzi scheme.

The Freakonomics Radio podcast delves into a 3-part series on repatriation called “Stealing Art Is Easy. Giving It Back Is Hard.” which includes interviews with many of the key players working in the field.

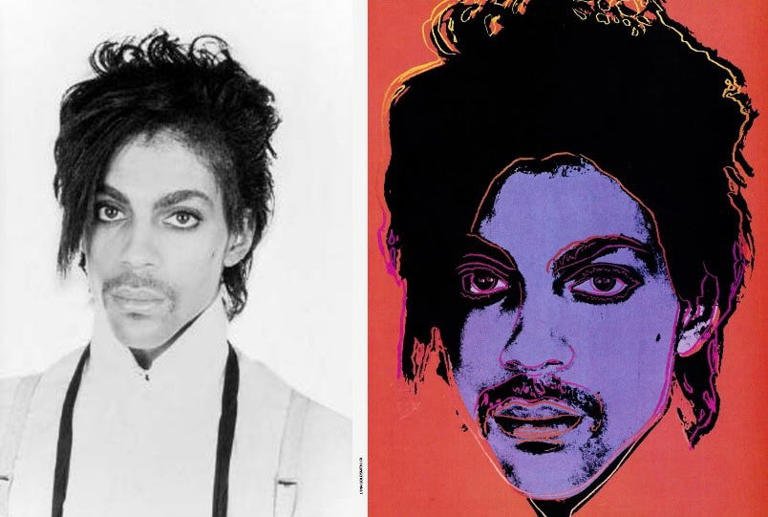

And, because I always have to include law-related items…. Andy Warhol continues to provoke seismic polarization and divisive polemic decades after his death. The Supreme Court of the United States decided to part the choppy intellectual property waters and sided against the Andy Warhol Foundation in a case regarding the use of Lynn Goldsmith’s photo of Prince.

I tried to come to my own conclusion on this and found it complicated to unpack. The case will tsunami intellectual property law and potentially establish a historic precedent for fair use cases. My investigation sourced some interesting opinions and analysis beyond basic reporting on the case but never really offered me a clear-cut opinion.

From Scotus Blog, Independent News and Analysis which focuses on the majority opinion written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

Sotomayor’s opinion characterizes the “fair use” defense as a central part of the copyright law’s “balancing act between creativity and availability.” For her, the first factor, the “character” of the later use, “relates to the problem of substitution,” and thus does not protect the later “use of an original work to achieve a purpose that is the same as, or highly similar to, that of the original work.” When the later work will “substitute for” or “supplant” the original work, as here, that factor cuts against the fairness of the later use.

This National Review take focuses on the vehemently dissenting Justice Elena Kagan’s opinion.

For it is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care. In adopting that posture of indifference, the majority does something novel (though in law, unlike in art, it is rarely a good thing to be transformative).

Separately…

The majority holds that because Warhol licensed his work to a magazine—as Goldsmith sometimes also did—the first factor goes against him. It does not matter how different the Warhol is from the original photo—how much “new expression, meaning, or message” he added. It does not matter that the silkscreen and the photo do not have the same aesthetic characteristics and do not convey the same meaning. It does not matter that because of those dissimilarities, the magazine publisher did not view the one as a substitute for the other. All that matters is that Warhol and the publisher entered into a licensing transaction, similar to one Goldsmith might have done. Because the artist had such a commercial purpose, all the creativity in the world could not save him.

The significance of the case stems from the fact that the majority opinion focused not on the transformative nature of Warhol’s work but on the fact that he licensed the image.

But in that case, there goes the basic notion behind appropriation art — that appropriation works because it does so little to alter its source.

This latter quote originates in the New York Times opinion questioning if the decision will hurt artists. It certainly leans toward the dissenting argument, and I do too. The reason is that Kagan’s written retort is inspired and even exciting prose. She dunks on her colleagues – with no interest in political affiliation – in favor of artistic practice.

More Good Kagan quotes:

“He reframed and reformulated—in a word, transformed—images created first by others. Campbell’s soup cans and Brillo boxes. Photos of celebrity icons: Marilyn, Elvis, Jackie, Liz—and, as most relevant here, Prince. That’s how Warhol earned his conspicuous place in every college’s Art History 101,” Kagan wrote, joined by Chief Justice John Roberts.

“It is not just that the majority does not realize how much Warhol added; it is that the majority does not care,” Kagan wrote.

The Art Newspaper address the fair use issue with both Warhol and Richard Prince in their “The Week in Art” podcast episode.

Lastly, prominent art advisor Lisa Schiff seems to have perfectly played her part in maintaining mainstream stereotypes of art world gluttony, corruption, and dishonestly and closed her New York firm following accusations of running a Ponzi scheme that fueled her lavish lifestyle.

Read an article about it here (many others confetti the internet).

What interests me more is how she would have run the Ponzi Scheme assuming the accusations play out given that at some point you have to provide the physical works of art. This Artnet article outlines the basics.

She takes client money to purchase a work (checks made out to her firm)

She engages the seller (mostly galleries it seems) to purchase

She does not pay them or only partially pays them

She uses the clients’ money to partially pay for other client purchases and otherwise roll like a celebrity

She owes money to many galleries

She keeps living the dream

Is it smart or dumb? Whatever the case, it makes for enthralling summer reading and provides us with a common villain at whom we point our fingers. Like Bernie Madoff, too, the number of prominent folks who simply trusted Schiff with their money and allowed her to control their collections astounds. It also shows the power of the work in that people will give up so much in order to get the pieces by way of gatekeepers such as Schiff. Very interesting.